The United Nations says one in three women will be beaten, coerced into sex or abused by a partner in her lifetime

Hours after nearly 1000 people marched in downtown Nairobi, Kenya, to protest against the rising rate of assault on women, it was reported that a Kenyan woman was stripped by a mob at a bus stop, after she was accused of “tempting” men because of her supposed “indecent” clothing.

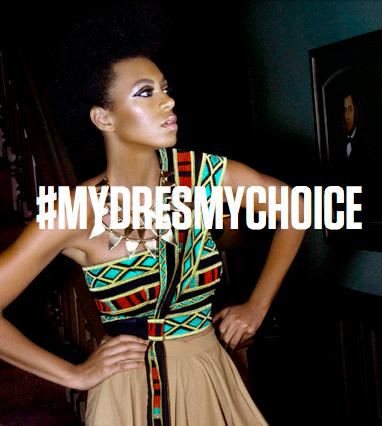

In the wake of the incident, women in Kenya have not been silent. In Kenya’s capital, Nairobi, women have been organizing and holding “miniskirt” marches—responding in masses. Besides showing up and turning up the volume at these marches, the online dialogue and hashtag campaign: #MydressMychoice is trending in Kenya —with a chorus of concerns, enraged and robust exchanges have been taking place.

The Kenya or any other African situation is not an anomaly —neither in the violation nor in the way women are responding to abuse and humiliating attacks perpetuated by a system that promotes such criminalizing conduct. Also, it important to point out, in the African context, “the erosion of the status of women occurred gradually but was significantly exacerbated and hastened by foreign invasions, particularly colonialism”. Having said that, let us be reminded that “violence and tolerance of violence are not endemic, not an “African tradition”, nor simply what black men do to women. Rather they are the results of systemic injustices”. And comparably, across the globe, similar, and at times much worse things are happening to women every day, often with impunity.

Amidst all the chaos, even without much backing from the courts or government, women are setting their own stage —fighting back to put an end to such chaos.

“Enough!” of the oppressive policies, maltreatment, harassment, body policing, and overall objectification of women, are the wide-range of sentiments heard. And even in a culture where responding may provoke backlashes —open up further prospects of threats and attacks, fearlessly courageous women who stand up for justice and freedom, have not be blocked.

Even though portrayed as invisible, women have been responding:

Just recently, in Ethiopia, we’ve heard the news of 16-year-old Hanna Lalango who died from gang rape in Addis-Ababa. The dreadful act, which put an end to an innocent teenage girl’s life, has created an outrage on social media under the hashtag campaign: #justiceforhanna, created by the “Yellow Movement” of Addis-Ababa University.

In Sudan, in 2009, a Sudanese woman, Lubna Ahmed Al-Hussein was arrested, found guilty and imprisoned for wearing trousers deemed “indecent”. During which Lubna had waived the immunity she had been granted as a United Nations worker and decided to have the trial continue –defending what she believes in. It was reported that she had said, “She is taking a stand to change the unconstitutional law which contradicts the peace accord terms.”

Ugandan women, in response to the signing by the Ugandan president of the anti-pornography bill — which, even if not explicitly, bans “indecent” dressing —have found ways to protest against it, even under circumstances where the police blocked them from doing so. They took to the streets of Kampala their stomping feet, banners and voice. Loudly, they were heard protesting: “my body, my business.”

Ugandan women, in response to the signing by the Ugandan president of the anti-pornography bill — which, even if not explicitly, bans “indecent” dressing —have found ways to protest against it, even under circumstances where the police blocked them from doing so. They took to the streets of Kampala their stomping feet, banners and voice. Loudly, they were heard protesting: “my body, my business.”

In Egypt, in the face of on-going harassment and systemic humiliation, Egyptian women, unwaveringly, are resisting and rising up to challenge a system that facilitates a culture of harassment and violence against women. Recently, women in prison, in response to the physical and psychological abuse women are subjected to in prisons, detention centers and police departments, have not been voiceless. Jointly with organizations that support their struggle, women are working to restructure a degrading system, and restore human dignity.

Using street art as a medium to respond to the large-scale gender-based street harassment —also applicable to off-street scenarios, a Brooklyn illustrator/ painter Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, in 2012, launched “stop telling women what to do” campaign. A public art project, the series of large-scale posters feature portraits of women with edifying anti-harassment captions. A campaign inspired and shaped by women’s experiences on the street, Fazlalizadeh interjected these pieces in public spaces, across various cities, to amplify and help spread the message, further.

The heart of the matter is this: in modern day, a system that operates from and supports patriarchal masculine constructs may be an obstacle, but it is not stopping women from responding to the various challenges.

Though women are advocating for themselves —it is not enough.

On all sides and all levels, we have to recognize and deconstruct how structural violence is playing out in our homes, communities, societies, countries and world –how it “manifests at interpersonal levels – in our homes and on our streets”. And how, the “male frustration and stress taken out on the tender bodies of women marks the worst dispossession of all – our dehumanization, the loss of our selves and our capacity to care for and support one another.”

Working further towards ending this incessantly perpetuated performance –a pattern of violence that’s structurally broad and deep, I believe men with political will would need to be engaged and be made part of the solution. And perhaps, if we work together towards creating a culture that guarantees will work for all, it may get us closer towards achieving a humanist solution. A solution that will lead to questioning and working towards eradicating a culture of violence against women that is part and parcel of a system that thrives from oppressive operations —pigeonholing of individuals. If we all take it as a personal conscientiousness, perhaps the struggle will amount to restoring human dignity. It is a journey that will require conscientious effort from all sides.